Lupine Seed High-Quality Vegan Protein

The standard North American diet tends to weigh in heavily with refined carbohydrates and sugars, as is widely known. Many people try to improve the protein content of their diet through supplementation with protein powder. At the same time, increasing numbers of people are choosing vegetarian or vegan diets. While there are many health benefits to these diets—for example, if done properly, they are high in fruits, vegetables, and legumes, and may reduce risk of ischemic heart disease, cancer, and other forms of chronic disease [1][2]—at the same time, common pitfalls and nutrient deficiencies may arise. One of these is protein deficiency, as well as that of iron, vitamin B12, zinc, vitamin D, and omega-3 fatty acids.[2][3]

Lupine seed is a high-quality, plant-derived protein source, ideal for vegetarians or vegans as well as others seeking to boost their protein intake. Although not well-known, lupines are legumes (beans), and the lupine family includes white lupine (Lupineus albus), yellow lupine (L. luteus) and narrow-leafed lupine (L. angustifolius).[4] The lupines are native European legumes that, according to a 2015 review, represent “a significant alternative to soya bean.”[4] Their seed protein content is high (up to 44%) and they represent a sustainably grown crop.[4]

Lupine also has a good amino-acid profile including all nine essential amino acids (*), with 30 g of lupine seed protein providing approximately:

- Glutamine 5.0 g

- Arginine 2.6 g

- Leucine* 1.6 g

- Lysine* 1.1 g

- Serine 1.1 g

- Glycine 1.0 g

- Valine* 0.9 g

- Tyrosine 0.8 g

- Alanine 0.8 g

- Threonine* 0.8 g

- Isoleucine* 0.8 g

- Histidine* 0.6 g

- Phenylalanine* 0.5 g

- Tryptophan* 0.2 g

- Methionine* 0.2 g

- Proline 0.1 g

In addition to its role as a protein source, lupine contains other constituents that have been the subject of investigation for their health benefits. The γ-conglutin protein fraction has been investigated for its potential effects in controlling insulin resistance and diabetes; lupine seeds are rich in the iron-containing protein ferritin; lupine protein is also thought to have possible effects on inflammation, regulation of the gut microbiome, and other metabolic parameters such as lipids and blood pressure.[4]

A number of studies have evaluated the effect of lupine protein supplementation on cholesterol. One randomized, double blind, placebo controlled (RCT) trial evaluated 72 adults with high cholesterol. Participants were randomized into three plans that included supplementation with 25 g daily lupine protein, 25 g daily milk protein, or milk protein plus 1.6 g arginine for 28 days. Lupine protein supplementation resulted in reductions in total cholesterol, LDL (“bad”) cholesterol, triglycerides, homocysteine (a marker of heart disease risk), and uric acid (which is associated with blood-glucose control).[5]

Another RCT evaluated the effect of 25 g lupine kernel fibre compared to citrus fibre or a low-fibre diet for four weeks.[6] Lupine fibre resulted in a 9% reduction to total cholesterol, 12% reduction in LDL, and 10% reduction in triglycerides compared to citrus fibre. Interestingly, lupine fibre was also associated with reduced high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation, and reduced systolic blood pressure when compared with baseline values.

Lupine supplementation was uniquely associated with an increase in short-chain fatty acids, especially acetate and propionate, which were hypothesized to mediate these effects at least in part. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are of interest, because they are thought to provide fuel to the cells lining the intestines, especially the large intestine or the colon.[7]

However, SCFAs are also taken up into the circulation and are used by various organs including the liver.[7] Similar results on cholesterol were found by a third study.[8]

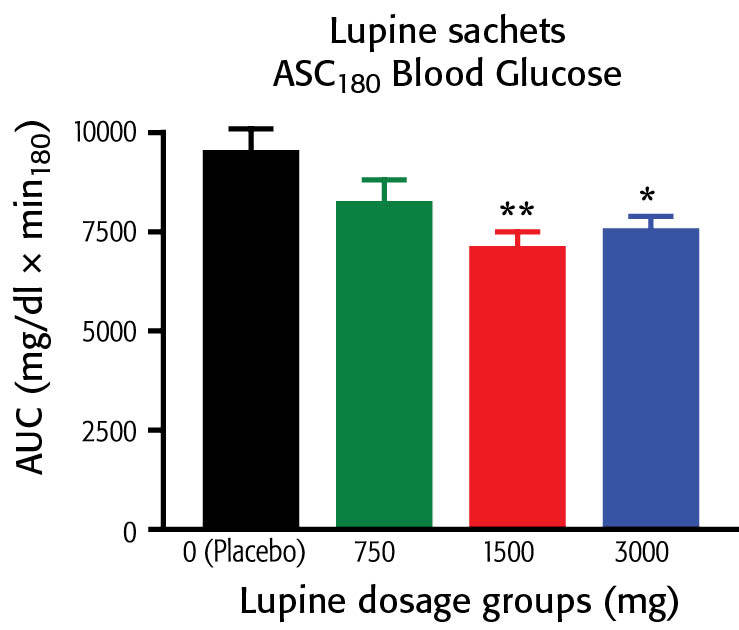

Another study evaluated the effect of lupine protein and one of its active constituents, γ-conglutin, on blood glucose control.[9] In a placebo-controlled trial of 15 healthy participants, one of three doses of lupine protein were administered, followed by carbohydrate loading. Blood glucose was measured over the next three hours. Compared to placebo, lupine protein doses of 1.5 g and 3.0 g (but not lower doses) were associated with lower increases in blood glucose associated with carbohydrate loading. This is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Hypoglycemic effect of Lupine (from Bertoglio 2011)

Another RCT in 24 patients with diabetes assessed the effect of lupine flour (containing 12.5 g lupine fibre plus 22 g lupine protein) on glucose control when consuming a drink containing 50 g glucose, compared to:

- Soy flour and glucose drink; and

- The glucose drink alone (control group).

After the glucose drink, blood glucose was significantly lower in both the lupine and the soy groups compared to the control group. Insulin and C-peptide levels were also higher for lupine and soya compared to control.[10]

Finally, an RCT evaluated the effects of lupine in 88 overweight and obese patients.[11] Participants were randomly assigned to replace 15–20% of their usual daily energy intake with white bread (control) or lupine kernel flour–enriched bread (lupine). For the lupine group, there was a small but significant reduction in systolic blood pressure (−3.0 mmHg), and reduction in pulse pressure (−3.5 mmHg).

Overall, the evidence summarized here indicates that there is a need for high-quality, plant-derived protein supplementation among large numbers of the population. Lupine seed contains all nine essential amino acids, and is relatively high in iron; in addition, lupine is a sustainable protein source. Lupine-seed protein supplementation has been shown to benefit cholesterol, blood glucose control, and blood pressure, and may also have anti-inflammatory effects as well as beneficial effects on the gut flora and production of short-chain fatty acids.

References

- Patel, H., et al. “Plant-based nutrition: an essential component of cardiovascular disease prevention and management.” Current Cardiology Reports, Vol. 19, No. 10 (2017): 104.

- Craig, W.J., Mangels AR; American Dietetic Association. “Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian diets.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association, Vol. 109, No. 7 (2009): 1266–1282.

- Agnoli, C., et al. “Position paper on vegetarian diets from the working group of the Italian Society of Human Nutrition.” Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases, Vol. 27, No. 12 (2017): 1037–1052.

- Lucas, M.M., et al. “The future of lupin as a protein crop in Europe.” Frontiers in Plant Science, Vol. 6 (2015): 705.

- Bähr, M., et al. “Consuming a mixed diet enriched with lupin protein beneficially affects plasma lipids in hypercholesterolemic subjects: a randomized controlled trial.” Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 34, No. 1 (2015): 7–14.

- Fechner, A., M. Kiehntopf, and G. Jahreis. “The formation of short-chain fatty acids is positively associated with the blood lipid-lowering effect of lupin kernel fiber in moderately hypercholesterolemic adults.” The Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 144, No. 5 (2014): 599–607.

- den Besten, G., et al. “The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism.” Journal of Lipid Research, Vol. 54, No. 9 (2013): 2325–2340.

- Weisse, K., et al. “Lupin protein compared to casein lowers the LDL cholesterol:HDL cholesterol-ratio of hypercholesterolemic adults.” European Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 49, No. 2 (2010): 65–71.

- Bertoglio, J.C., et al. “Hypoglycemic effect of lupin seed γ-conglutin in experimental animals and healthy human subjects.” Fitoterapia, Vol. 82, No. 7 (2011): 933–8.

- Dove, E.R., et al. “Lupin and soya reduce glycaemia acutely in type 2 diabetes.” The British Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 106, No. 7 (2011): 1045–1051.

- Lee, Y.P., et al. “Effects of lupin kernel flour-enriched bread on blood pressure: A controlled intervention study.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 89, No. 3 (2009): 766–772.

Dr. Philip Rouchotas, MSc, ND

Dr. Philip Rouchotas, MSc, ND

Well-known in the community as a naturopathic doctor, associate professor, and editor-in-chief of Integrated Healthcare Practitioners.

Stores

Stores

Dr. Heidi Fritz, MA, ND

Dr. Heidi Fritz, MA, ND