What Is Leaky Gut?

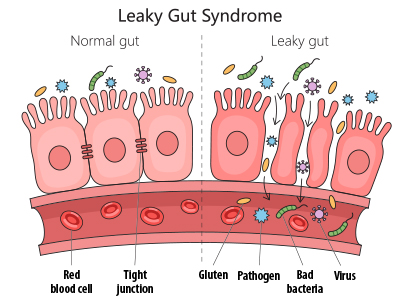

A healthy intestinal tract is made of two layers of cells which are responsible for governing what is absorbed into the bloodstream and lymphatic vessels from the gastrointestinal tract and what is eliminated in a bowel movement. In a healthy intestinal tract, the adjacent cells that form the absorptive lining are connected to one another through structures known as tight junctions. Imagine the lining of your intestines is a quilt where each intestinal cell is represented by a single square in the quilt and each square is stitched together with thread—those stitches are the tight junctions. It is these tight junctions that help ensure that we absorb only what is desired in the intestines (vitamins, minerals, dietary fat, carbohydrates, etc.) while the rest is eliminated as waste.[1]

When tight junctions become damaged, the result is the development of gaps between adjacent intestinal cells.

The disruption in the tight junctions is known as intestinal hyperpermeability or, more commonly, leaky gut. The hyperpermeability that characterizes leaky gut creates breaches in the intestinal wall, which may then allow for the absorption of harmful substances like bacteria, toxins, or undigested food particles. Once absorbed, these toxins can reach the bloodstream where they can trigger an inflammatory response which can adversely impact the hormonal, immune, nervous, respiratory, or reproductive systems.[2] The inflammation associated with leaky gut has been associated with intestinal disorders like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), and liver cirrhosis. Additionally, leaky gut has been related to diseases that outside of the intestines including diabetes mellitus, obesity, heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and more.[3]

Where Does Leaky Gut Come From?

The integrity of the gut lining and its tight junctions depends heavily on the status of the microbiota (the array of bacteria that reside in the intestines) as well as the layer of mucus that coats and protects the intestinal lining. The interactions between the gut microbiota and the immune system are significant for reducing inflammation and for stabilizing the tight junctions.[4] The mechanisms through which the intestinal microbiota help reduce intestinal permeability are many and include reducing the growth of disease-causing bacteria and the production of short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, which help reduce local inflammation and serve as a fuel source of the intestinal cells. A disruption in the gut microbiota (dysbiosis), for example infection with Helicobacter pylori, can result in disruption of tight junctions.[5]

In addition to alterations in the gut microbiota, pharmaceuticals have been associated with the onset of leaky gut. Drugs such as antibiotics as well as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, or paracetamol damage the mucosal layer of the stomach and intestines. Long-term use of these categories of drugs is associated with an increase in intestinal permeability.[6]

Diet is yet another factor implicated in the development of leaky gut. What we consume plays a major role in influencing the function of the gut and the composition of the microbiota. Several studies have shown that the consumption of simple sugars (fructose, glucose, and sucrose) is implicated in increased intestinal permeability and in dysfunction of the tight junctions. On the other hand, some carbohydrates—namely complex carbohydrates (fibre)—can support the growth of beneficial bacteria and are known to positively affect intestinal permeability.[7] Dietary fibre is broken down by enzymes and fermented by microorganisms, producing short-chain fatty acids like butyrate and propionate, which play key roles in protecting the intestines. Alcohol consumption has been found to degrade the mucous layer in the intestines, which is critical for intestinal-barrier function. As such, alcohol use is another contributor to the development of leaky gut.[8]

Diet is yet another factor implicated in the development of leaky gut. What we consume plays a major role in influencing the function of the gut and the composition of the microbiota. Several studies have shown that the consumption of simple sugars (fructose, glucose, and sucrose) is implicated in increased intestinal permeability and in dysfunction of the tight junctions. On the other hand, some carbohydrates—namely complex carbohydrates (fibre)—can support the growth of beneficial bacteria and are known to positively affect intestinal permeability.[7] Dietary fibre is broken down by enzymes and fermented by microorganisms, producing short-chain fatty acids like butyrate and propionate, which play key roles in protecting the intestines. Alcohol consumption has been found to degrade the mucous layer in the intestines, which is critical for intestinal-barrier function. As such, alcohol use is another contributor to the development of leaky gut.[8]

Lastly, stress and certain conditions associated with stress—such as intense endurance exercise, depression, and physiological changes during pregnancy—have been linked to increased intestinal permeability.[9] With stress, inflammation levels rise due to the release of chemicals like histamine. In response to stress-induced inflammation, the hormone cortisol is produced to help the body adapt to the stressor. Chronically elevated levels of both cortisol and histamine have been shown to increase in intestinal permeability.[10]

What Can You Do to Address Leaky Gut?

As we have seen, leaky gut can develop for many reasons, and there are various ways to address it. Here are a few key strategies to support the health of your intestinal tight junctions.

As we have seen, leaky gut can develop for many reasons, and there are various ways to address it. Here are a few key strategies to support the health of your intestinal tight junctions.

Reduce stress, as much as you can. If you cannot eliminate a stressor, develop some tools to help lessen the impact of stress on your body, such as breathing exercises, grounding techniques, meditation, or adopting a creative outlet (journaling, painting, singing).

Adopt a gut-friendly diet that is low in simple sugars and alcohol and that is rich in fibre, plant-based foods, and fermented foods. Plants are rich in compounds known as polyphenols, which are associated with a greater diversity of gut-friendly bacteria. Polyphenols also enhance tight-junction integrity, increase mucus secretion, and decrease intestinal-barrier permeability, thereby generally improving the intestinal defense mechanism.[11] Fibre serves as the preferred food for the beneficial gut bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria. Increasing fibre intake supports a healthy microbiome by promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria. Moreover, as previously mentioned, the intestine’s microbiota ferment dietary fibre, creating short-chain fatty acids which nourish the cells of the intestinal lining and help reduce inflammation that could otherwise disrupt the integrity of tight junctions.[12], [13]

Consider Supplementation

Antioxidant vitamins including vitamins A and D are important in maintaining tight junctions. In the intestines, in vitro studies show that vitamins A and D improve the tight junctions. Both vitamins are needed for the integrity of the epithelium: They support the gut microbiota and help reduce intestinal inflammation.[14], [15]

Antioxidant vitamins including vitamins A and D are important in maintaining tight junctions. In the intestines, in vitro studies show that vitamins A and D improve the tight junctions. Both vitamins are needed for the integrity of the epithelium: They support the gut microbiota and help reduce intestinal inflammation.[14], [15]

ʟ‑Glutamine is a crucial amino acid capable of regulating the expression of tight junction proteins. ʟ‑Glutamine helps reduce intestinal inflammation, thus allowing the membrane of intestinal cells to remain impermeable.[16], [17]

Zinc carnosine appears to support intestinal barrier function by acting as an antioxidant. A clinical trial of oral zinc carnosine showed that it prevented the rise in gut permeability caused by clinical doses of the NSAID indomethacin.[18]

The disruption of the barrier function of the intestinal tract is an important driver for an array of health conditions including irritable bowel syndrome, obesity, and dementia. As we have reviewed, many reasons contribute to the development of leaky gut. As such, it is crucial to work with a trained medical professional who is experienced with and capable of assessing through appropriate diagnostic testing to determine if leaky gut is a contributor to your current health condition. More importantly, consult with a trained medical professional prior to beginning any supplement regime to address leaky gut to ensure the supplements you are considering are both safe and appropriate for you to use.

Dr. Colleen Hartwick, ND

Dr. Colleen Hartwick, ND

Dr. Colleen Hartwick is a licensed naturopathic physician practising on North Vancouver Island, BC, with a special interest in trauma as it plays a role in disease.

campbellrivernaturopathic.com

References

[1] Aleman, R.S., M. Moncada, and K.J. Aryana. “Leaky gut and the ingredients that help treat it: A review.” Molecules, Vol. 28, No. 2 (2023): 619.

[2] Obrenovich, M.E.M. “Leaky gut, leaky brain?” Microorganisms, Vol. 6, No. 4 (2018): 107.

[3] Aleman, Moncada, and Aryana, op. cit.

[4] Yoo, J.Y., M. Groer, S.V.O. Dutra, A. Sarkar, and D.I. McSkimming. “Gut microbiota and immune system interactions.” Microorganisms, Vol. 8, No. 10 (2020): 1587.

[5] Carding, S., K. Verbeke, D. Vipond, B. Corfe, and L. Owen. “Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease.” Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, Vol. 26 (2015): 26191.

[6] Aleman, Moncada, and Aryana, op. cit.

[7] Binienda, A., A. Twardowska, A. Makaro, and M. Salaga. “Dietary carbohydrates and lipids in the pathogenesis of leaky gut syndrome: An overview.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Vol. 21, No. 21 (2020): 8368.

[8] Aleman, Moncada, and Aryana, op. cit.

[9] Camilleri, M. “Leaky gut: Mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans.” Gut, Vol. 68, No. 8 (2019): 1516–1526.

[10] Madison, A., and J.K. Kiecolt‑Glaser. “Stress, depression, diet, and the gut microbiota: Human-bacteria interactions at the core of psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition.” Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 28 (2019): 105–110.

[11] Kaulmann, A., and T. Bohn. “Bioactivity of polyphenols: Preventive and adjuvant strategies toward reducing inflammatory bowel diseases-promises, perspectives, and pitfalls.” Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, Vol. 2016 (2016): 464–470.

[12] Aleman, Moncada, and Aryana, op. cit.

[13] Kaulmann and Bohn, op. cit.

[14] Aleman, Moncada, and Aryana, op. cit.

[15] Raftery, T., A.R. Martineau, C.L. Greiller, S. Ghosh, D. McNamara, K. Bennett, J. Meddings, and M. O’Sullivan. “Effects of vitamin D supplementation on intestinal permeability, cathelicidin and disease markers in Crohn’s disease: Results from a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study.” United European Gastroenterology Journal, Vol. 3, No. 3 (2015): 294–302.

[16] Aleman, Moncada, and Aryana, op. cit.

[17] Kretzmann, N.A., H. Fillmann, J.L. Mauriz, C.A. Marroni, N. Marroni, J. Gonzalez‑Gallego, and M.J. Tunon. “Effects of glutamine on proinflammatory gene expression and activation of nuclear factor kappa B and signal transducers and activators of transcription in TNBS-induced colitis.” Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Vol. 14, No. 11 (2008): 1504–1513.

[18] Playford, R.J., and T. Marchbank. “Oral zinc carnosine reduces multi-organ damage caused by gut ischemia/reperfusion in mice.” Journal of Functional Foods, Vol. 78 (2021): 104361.

Stores

Stores