The Gut–Lung Microbiome Axis: A Bidirectional Immune Highway

By now, most of us have heard the word microbiome—the collection of trillions of functional bacteria of all different species found in many places throughout our bodies, such as our skin, gut, mouth, vagina, and lungs. Whether you are a health-care practitioner or just watching TV when a popular body-wash company commercial comes on—advertising about how their soap is good for your skin microbiome—one way or another, I’m sure you have heard it!

In research, health-care media, and health-care professions, a lot of emphasis is placed on our intestinal microbiome and its impact on our health—as there should be! Our gut microbiome plays so many roles in our health and affects a plethora of systems in our body: immunity, neurotransmitter production, vitamin production, mood regulation, brain health, inflammation levels, iron status, biochemical pathways, etc.

Now, research is starting to build on the topic of the lung microbiome and the gut–lung axis. Let’s explore.

The human body is estimated to be colonized by around 38 trillion bacteria,[1] with the colon housing the densest and most metabolically active populations of bacteria.[2]

The human body is estimated to be colonized by around 38 trillion bacteria,[1] with the colon housing the densest and most metabolically active populations of bacteria.[2]

Having a diverse colony of bacteria has been shown to be paramount for optimal health overall, not just intestinal health.

Of particular interest for this article is that studies have linked having a reduced microbial diversity to having a predisposition to allergic airway diseases.[3] Having reduced microbial diversity can be seen after antibiotic usage, in people who suffer multiple childhood episodes of moderate-severe diarrhea, and in cases of malnutrition, to provide a few examples.[4]

Studies have also shown that this reduced intestinal microbial diversity leads to an increased risk of airway diseases such as asthma, and to an increased predisposition to pulmonary viral infections.[3]

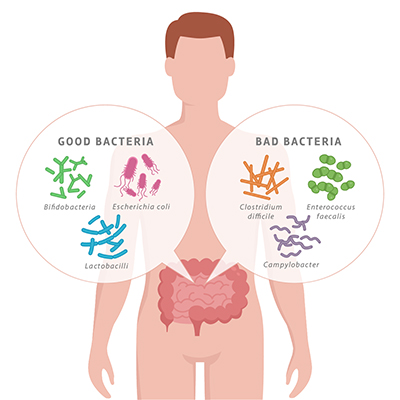

The gut microbiome is influenced through diet, stress, exercise, infections, medications, nutrition, digestive conditions, travel, environment, and more. All of these factors have potential for shifting the gut microbiome towards overgrowth of more harmful bacteria species than beneficial species, or vice versa (depending on the factor).

The gut microbiome is influenced through diet, stress, exercise, infections, medications, nutrition, digestive conditions, travel, environment, and more. All of these factors have potential for shifting the gut microbiome towards overgrowth of more harmful bacteria species than beneficial species, or vice versa (depending on the factor).

This outgrowth of harmful bacteria v. beneficial bacteria is termed dysbiosis and can have a negative impact on both gastrointestinal as well as overall health. Of particular interest for this article is the impact that dysbiosis has on our respiratory system.

The lung was previously thought to be a sterile environment, and we now know that this is not the case.[5] In addition to being formed upon our first breaths as neonates, the lung microbiome is suggested to be partially formed through breathing in bacterial colonies from our mouth during sleep, when the muscles and tissues in our mouth and throat relax, and our deep breathing during sleep transmits the microbes deeper into the bronchial tree.[5]

This lung microbiome is dynamic and, throughout our life, is influenced by the gut microbiome, and vice versa.[5] This bidirectional communication is termed the gut–lung axis and is gaining traction in the research world.

This gut–lung connection is portrayed well through data stating that 50% of patients suffering from inflammatory bowel disease and dysbiosis also have decreased lung function.[5]

In addition to this, studies have shown that respiratory infections, like the influenza virus, can lead to altered gut microbiota and gastrointestinal issues.[5]

This bidirectional loop between the gut and the lungs influencing each other’s microbiome is primarily through the bacteria acting as signaling molecules.[6] Our gut bacteria play a protective role against bacterial and viral pulmonary infections, by regulating our immune response through the stimulation of immune cells in lymph fluid and bone marrow.[3]

The bacteria in the gut use signaling to stimulate immune cells, which then travel through the mesenteric lymph nodes in the gut, via lymph fluid, to lymph nodes in the respiratory system, where immunological information is passed on from gut to lung and vice versa.[6]

The bacteria in the gut use signaling to stimulate immune cells, which then travel through the mesenteric lymph nodes in the gut, via lymph fluid, to lymph nodes in the respiratory system, where immunological information is passed on from gut to lung and vice versa.[6]

There are also more direct ways that gut bacteria can influence lung bacteria. Although lymph nodes in the gut neutralize most bacteria, remaining surviving bacteria and bacterial fragments travel via the lymph system into systemic circulation, where they can then modulate the immune response in the lung.[6] This process also occurs in the opposite direction from the lung to the gut.

We can now see how the lung and gut form part of our immune system, and how an inflammatory response or infection or dysbiosis in one of these organs may be mirrored in the other.[6]

Another important factor in the modulation of the lung immune system through the gut microbiota is via short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).[6] Gut bacteria digest dietary fibres and produce metabolites called SCFAs, like butyrate and propionate, as a result. These SCFAs have multiple functions in our bodies: They provide fuel to our intestinal cells to help them thrive and function, serve as fuel for the mitochondria in our bodies to provide energy, strengthen the intestinal lining, and have anti-inflammatory effects in the gut and the respiratory system. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) strengthen the lining of our intestines through fortification of things called tight junctions—meaning they help to reduce intestinal permeability.[6] Butyrate (an SCFA) also works by stimulating anti-inflammatory signaling, which can suppress inflammation in the intestines and inflammation-related colon cancer.[6]

These SCFAs elicit their effect on the immune system of the lung by way of travelling from the gut into the bloodstream, then into the bone marrow, where they stimulate a cascade that leads to enhanced metabolism of immune cells, and therefore enhanced activation of these specific immune cells that have antiviral activity in the lung.[6]

Let’s summarize all that dense information.

The connection between our gut and our lungs is intricate and bidirectional. An infection, a dysbiosis, or an inflammation in one environment mirrors in the other (e.g. irritable bowel disease [IBD] and dysbiosis are associated with reduced lung function, or the influenza virus causing gut dysbiosis and gastrointestinal issues).[6] Bacteria and metabolites of bacteria (SCFAs) govern this connection. The communication between the lungs and the gut occurs through systemic circulation of blood or lymph flow, which contain SCFAs (which activate immune cells and are anti-inflammatory), immunological information, bacteria, and bacterial fragments.[6]

Now, let’s go over some (not all!) important factors to consider when trying to keep our guts healthy.

First and foremost: Follow nutritional advice, supplemental advice, lifestyle advice, etc. that is right for you and your body.

First and foremost: Follow nutritional advice, supplemental advice, lifestyle advice, etc. that is right for you and your body.

Online information—including this article—should only serve as a relative guide. Personalized and individualized care is crucial for your health, so make sure you see a naturopathic doctor (ND) to address your concerns.

A healthy, balanced diet full of whole foods, including lots and lots of vegetables of all kinds and all colours, is a critical foundational pillar in gut health.

Don’t exclude high-carbohydrate or starchy vegetables: Avoiding starchy or high-carbohydrate vegetables means you are starving out very important beneficial bacteria that thrive on these types of vegetables and their fibres. These beneficial bacteria produce the very important SCFAs that we discussed upon digestion of these fibres.

Work with an ND to ensure your diet is right for you, your goals, and your body.

Stress has a negative impact on the diversity and balance of our microbiome, so stress management is paramount in gut health. Your ND can help!

Avoiding foods that can create dysbiosis and inflammation, like sugars, artificial sweeteners, refined foods, processed foods, simple refined grains, and other inflammatory foods that you identify as triggers for your body (work with your ND to identify these).

Prebiotic food sources (if your system is ready to handle them—they may aggravate some conditions) feed the healthy bacteria in your gut. Some sources include whole ginger root, onions, raw garlic, and under-ripe bananas.

Prebiotic food sources (if your system is ready to handle them—they may aggravate some conditions) feed the healthy bacteria in your gut. Some sources include whole ginger root, onions, raw garlic, and under-ripe bananas.

If it is right for you, probiotic food sources or supplements introduce beneficial bacteria to your gut. Again, work with your ND, because these can be aggravating to some issues if used incorrectly.

Dr. Elena Zarifis, BSc.(Hons), ND

Dr. Elena Zarifis, BSc.(Hons), ND

A licensed naturopathic doctor in Oakville and Burlington, Ontario, with a special interest in gut, brain, thyroid, and overall hormone health.

drelenaznd.com

References

- Sender, R., S. Fuchs, and R. Milo. “Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body.” PLoS Biology, Vol. 14, No. 8 (2016): e1002533.

- Donaldson, G.P., S.M. Lee, and S.K. Mazmanian. “Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota.” Nature Reviews. Microbiology, Vol. 14, No. 1 (2016): 20–32.

- Dang, A.T., and B.J. Marsland. “Microbes, metabolites, and the gut–lung axis.” Mucosal Immunology, Vol. 12, No.4 (2019): 843–850.

- Rouhani, S., et al. “Diarrhea as a potential cause and consequence of reduced gut microbial diversity among undernourished children in Peru.” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 71, No. 4 (2020): 989–999.

- Wypych, T.P., L.C. Wickramasinghe, and B.J. Marsland. “The influence of the microbiome on respiratory health.” Nature Immunology, Vol. 20, No. 10 (2019): 1279–1290.

- Anand, S., and S.S. Mande. “Diet, microbiota and gut–lung connection.” Frontiers in Microbiology, Vol. 9 (2018): 2147.

Stores

Stores