The Gut-Brain Axis - Probiotics And Mental Health

The role of probiotics in gastrointestinal health has been clearly demonstrated in recent research and is an emerging area of interest.

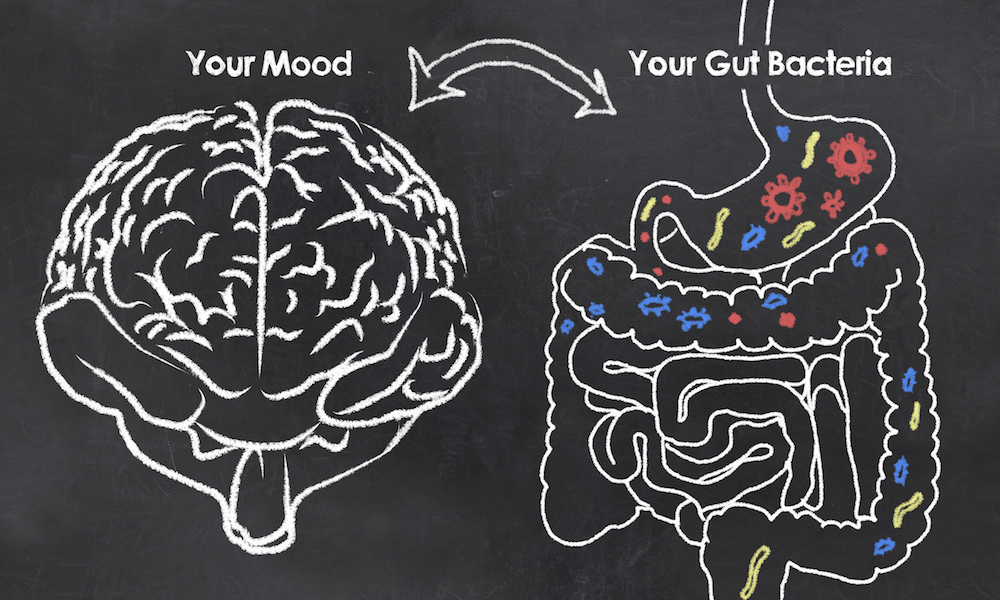

Several clinical trials have examined the effects of probiotic supplementation on mental health, including anxiety and depression, and have shown effects on brain activity and information processing, as well as hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responsiveness. Animal studies show that enteric (gut) bacteria may impact mood, in part through effects on the autonomic nervous system which is present in the gut—for instance, vagal nerve activity, intestinal barrier function and permeability, as well as modulation of HPA reactivity. Highlights from these studies are summarized below.

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 70 subjects were treated with either 100 g of conventional (containing no probiotic) yogurt and one placebo capsule, 100 g of probiotic yogurt and one placebo capsule, or 100 g of probiotic yogurt and one probiotic capsule, daily for six weeks.[1] After six weeks, subjects who received either the yogurt containing probiotic or the probiotic capsule experienced significant improvements in their general health score as well as their depression, anxiety, and stress scale score. There was no significant change in the conventional yogurt group.

Two randomized, placebo-controlled trials demonstrated anxiety-lowering effects in animals and humans following administration of a probiotic formulation (PF) consisting of Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175.[2, 3] In humans, supplementation with probiotics for 30 days was found to reduce ratings of psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and anger/hostility. There was also a significant reduction in urinary cortisol.

In patients under stress due to undergoing surgery for laryngeal cancer, supplementation with probiotics was shown to blunt the stress-associated increase in cortisol-releasing factor (CRF) and decreased ratings of anxiety compared to placebo.[4] Another study found that supplementation with a prebiotic was associated with a lower salivary cortisol awakening response, compared with placebo.[5] This data suggests that enteric bacteria may be associated with a decrease in the neuroendocrine response to stress, and may have anxiolytic effects.

Another study found that probiotic supplementation alters brain processing, including processing of emotional and sensory input.[6] Supplementation with a fermented milk product containing probiotic was associated with improvements in connectivity and communication within the brain as measured by MRI, which researchers theorized may be linked to anxiety-lowering effects.

Studies have also demonstrated benefit on anxiety among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome,[7] and improvement of mood among patients with depression.[8]

Together, this evidence suggests that probiotics may improve mood and anxiety by modulating stress-responsive HPA axis reactivity, and improving brain processing of emotional input. Other ways probiotics may affect mental health include the modulation of intestinal permeability and intestinal nervous system function, as well as the production of various molecules such as cytokines and neurotransmitters that affect brain function.[9–12] This emerging data on the link between enteric bacteria and neuroendocrine function positions probiotics as new therapeutic agents in the field of naturopathic psychiatry.

References

- Mohammadi, A.A., et al. “The effects of probiotics on mental health and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in petrochemical workers.” Nutritional Neuroscience 2015 Apr 16. [Epub ahead of print]

- Messaoudi, M., et al. “Beneficial psychological effects of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in healthy human volunteers.” Gut Microbes Vol. 2, No. 4 (2011): 256–261.

- Messaoudi, M., et al. “Assessment of psychotropic-like properties of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in rats and human subjects.” British Journal of Nutrition Vol. 105, No. 5 (2011): 755–764.

- Yang, H., et al. “Probiotics reduce psychological stress in patients before laryngeal cancer surgery.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology Vol. 12, No. 1 (2016): e92–e96.

- Schmidt, K., et al. “Prebiotic intake reduces the waking cortisol response and alters emotional bias in healthy volunteers.” Psychopharmacology Vol. 232, No. 10 (2015): 1793–1801.

- Tillisch, K., et al. “Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity.” Gastroenterology Vol. 144, No. 7 (2013): 1394–1401, 1401.e1–4.

- Rao, A.V., et al. “A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of a probiotic in emotional symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome.” Gut Pathogens Vol. 1, No. 1 (2009): 6.

- Benton, D., C. Williams, and A. Brown. “Impact of consuming a milk drink containing a probiotic on mood and cognition.” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition Vol. 61, No. 3 (2007): 355–361.

- Arseneault-Bréard, J., et al. “Combination of Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175 reduces post-myocardial infarction depression symptoms and restores intestinal permeability in a rat model.” British Journal of Nutrition Vol. 107, No. 12 (2012): 1793–1799.

- Bercik, P., et al. “The anxiolytic effect of Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 involves vagal pathways for gut-brain communication.” Neurogastroenterology and Motility Vol. 23, No. 12 (2011): 1132–1139.

- Desbonnet, L., et al. “The probiotic Bifidobacteria infantis: An assessment of potential antidepressant properties in the rat.” Journal of Psychiatric Research Vol. 43, No. 2 (2008): 164–174.

- Sudo, N., et al. “Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice.” Journal of Physiology Vol. 558 (Part 1): 263–275.

Stores

Stores