Digestion 101

Welcome to Digestion 101! To start, I would like you to think of your body as a donut. Not the cream-filled ones; the traditional hole-in-the-middle donut. Now, imagine taking a cross section of it. The thin baked outer part represents your skin; the fluffy baked dough on the inside represents your other internal organs, bones, blood, muscles, glands, etc.; and the hole in the middle represents your digestive tract, going from your mouth to your anus. Just like your skin, the digestive tube creates a barrier between you and the outside. So, much of your immune system lies right there inside that digestive tract.[i]

To run through, from top to bottom: We chew food in our mouths as it mixes with saliva, we swallow and it travels down the oesophagus, entering into the stomach. Here, powerful muscles and acid start protein digestion and kill unwanted microbes. As the food sludge leaves the stomach and enters the duodenum (first part of the small intestine), the pancreas adds in digestive enzymes and the gall bladder squeezes to release bile, aiding in fat digestion.

The small intestine is the major area for nutrient absorption and has a lot of infoldings to maximize surface area. Next, this liquid food moves into the large intestine or colon where the majority of the microbiome lies. Most of the water is absorbed into the body along this part of the journey, forming a solid stool, and is finally eliminated as waste through the anus.

A healthy digestive system allows for proper breakdown of food into nutrients that the body can use for energy, growth, immunity, mood, and mental health. When things are out of balance, we can experience discomfort, nutrient deficiencies, and chronic health issues. Some of the signs of poor digestion include bloating and gas; stomach aches or cramping; heartburn or acid reflux; constipation or diarrhea; brain fog; fatigue; changes in weight; and even skin issues such as eczema, psoriasis, acne, or rashes can be related to the health of your gut. More recent studies are looking at the role of the gut flora on diabetes, difficulty losing weight, and mental illnesses. Other, more serious health conditions related to the digestive system are inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) such as Crohn’s and colitis, celiac disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), gall stones, pancreatic insufficiency, and a variety of cancers. Let’s look at a few!

Acid Reflux

The first thing I would like to point out is that acid reflux is not usually a problem of too much acid: it’s a problem of location. The stomach lining is designed to handle a lot of acid, but when contents spurt upwards, it burns the lining of the oesophagus that is not equipped to deal with acid. Antiacid medications, such as proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), are often prescribed to decrease acidity, but they aren’t always the best long-term solution. Having low stomach acid for a long time can lead to other problems, such as unwanted bacteria entering the digestive system causing small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) [ii] or dysbiosis (imbalance in the microflora), or the inability to efficiently absorb vitamins and minerals, leading to deficiencies. A thorough workup with testing is important to figure out the root cause. Acid reflux can look like a variety of things, so testing the cardiovascular system, the respiratory system, doing an endoscopy, and testing for Helicobacter pylori should all be considered. Supporting stress, correcting breathing, and testing for SIBO are also important in treatment.

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth

Probiotics are not always the solution to your digestive issues! Bacteria—both in the body and in probiotic capsules—are measured in colony-forming units (CFU). There is an abundance of bacteria in the mouth (10⁶ CFU/ml) and in the colon (10⁹ CFU/ml). However, the acidity of the stomach keeps bacterial counts low (< 100 CFU/ml) and the small intestine is comparable (< 1000 CFU/ml); much lower than the large intestine.[iii] Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is a condition where there is actually too much bacteria (good or bad), inhabiting the small intestine.[iv] This creates fermentation too high up in the digestive tract, causing bloating and discomfort,[v] and is often related to irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). There are a variety of reasons that SIBO occurs, but the risk of developing it is higher in inflammatory bowel diseases, problems with motility, low stomach acid, and gall-bladder removal, to name a few.[vi]

To test for SIBO is a challenge, because accessing the small intestine is not easy. Currently available are breath tests,[vii], [viii] such as the lactulose breath test,[ix] measuring gases (hydrogen, methane, and hydrogen sulfide) to get an idea of what types of bacteria are overgrowing. Also important to note: Bacteria living together in the intestines naturally produce a protective layer called a biofilm. This happens in your bathroom sink and on your teeth, if you don’t clean regularly. So, in order to treat SIBO, we have to use a “biofilm opener” supplement to get access to the bacteria and strong antimicrobials or antibiotics to kill the bacterial overgrowth. Biofilm openers include NAC, ALA, and black cumin seed extract, or a specific combination of products. Oregano, thyme, goldenseal, berberis, and garlic are a few examples of antimicrobial herbs, while antibiotics such as rifaximin may also be used as treatment.[x], [xi] It is of utmost importance to test first and definitely do not experiment on your own. I would highly recommend seeing a naturopathic doctor (ND) with specialized training in SIBO for a comprehensive plan.

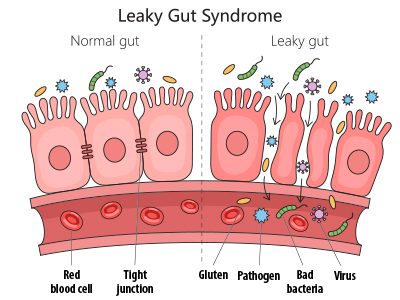

Hyperpermeability, aka Leaky Gut

To support digestion, NDs often use functional tests that are not always indicative of an illness. Various tests using stool samples are available to see the types of bacteria that may be living in your colon. Important measures are the quantity and quality of bacteria, the presence of pathogens or parasites (bacterial, viral, yeast, protozoa, and worms), inflammatory markers (calprotectin), and assessment for hyperpermeability (zonulin). Leaky gut means there are spaces in between the cells of the intestinal wall, allowing larger-than-normal particles to pass through. This can cause a variety of problems such as pain, cramping, food sensitivities, and immune reactions. Studying intestinal permeability is quite complex, but research is finding relationships with leaky gut and autoimmune diseases, autism, metabolic conditions (diabetes, obesity, and liver disease), and neurological diseases.[xii] The base support for leaky gut is to strengthen the intestinal wall using colostrum or an amino acid called glutamine. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, it was found that glutamine supplements dramatically improved IBS symptoms and rarely produced negative events.[xiii] Zonulin is a test marker for permeability, and in a small study on athletes, all the measures went back to normal after 20 days of colostrum supplementation.[xiv]

The digestive tract is definitely an intricate donut hole, and although I separated a few conditions, nothing ever happens alone. Billions of bacteria communicate, and this system is closely connected with the rest of the body. In all the ways to support overall health, in my opinion, the digestive tract is central.

Dr. Krista Mackay, BSc, ND

Krista practices both in Montreal, Quebec, and Montevideo, Uruguay. A busy mom of two boys, she focuses on naturopathic general/family medicine, helping to find a reasonable balance to optimal wellbeing and stress management, including nutrition, herbal medicine, and mind-body work.

kristamackay.ca

References

[i] Di Tommaso, N., A. Gasbarrini, and F.R. Ponziani. “Intestinal barrier in human health and disease.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 18, No. 23 (2021):12836.

[ii] Sharabi, E., and A. Rezaie. “Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.” Current Infectious Disease Reports, Vol. 26 (2024): 227–233.

[iii] Sharabi and Rezaie, op. cit.

[iv] Rezaie, A., M. Pimentel, and S.S. Rao. “How to test and treat small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: An evidence-based approach.” Current Gastroenterology Reports, Vol. 18, No. 2 (2016): 8.

[v] Rezaie, Pimentel, and Rao, op. cit.

[vi] Sharabi and Rezaie, op. cit.

[vii] Rezaie, Pimentel, and Rao, op. cit.

[viii] Goshal, U.C. “How to interpret hydrogen breath tests.” Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, Vol. 17, No. 3 (2011): 312–317.

[ix] Li, L., X.‑Y. Zhang, J.‑S. Yu, H.‑M. Zhou, Y. Qin, W.‑R. Xie, W.‑J. Ding, and X.‑X. He. “Ability of lactulose breath test results to accurately identify colorectal polyps through the measurement of small intestine bacterial overgrowth.” World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Vol. 15, No. 6 (2023): 1138–1148.

[x] Pimental, M. “Review of rifaximin as treatment for SIBO and IBS.” Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs, Vol. 18, No. 3 (2009): 349–358.

[xi] Gatta, L., and C. Scarpignato. “Systematic review with meta-analysis: Rifaximin is effective and safe for the treatment of small intestine bacterial overgrowth.” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, Vol. 45, No. 5 (2017): 604–616.

[xii] Di Tommaso, Gasbarrini, and Ponziani, op. cit.

[xiii] Zhou, Q.Q., M.L. Verne, J.Z. Fields, J.J. Lefante, S. Basra, H. Salameh, and G.N. Verne. “A randomized placebo-controlled trial of dietary glutamine supplements for post‑infectious irritable bowel syndrome.” Gut, Vol. 68, No. 6 (2018): 996–1002.

[xiv] Hałasa, M., D. Maciejewska, M. Baśkiewicz‑Hałasa, B. Machaliński, K. Safranow, and E. Stachowska. “Oral supplementation with bovine colostrum decreases intestinal permeability and stool concentrations of zonulin in athletes.” Nutrients, Vol. 9, No. 4 (2017): 370.